Regimes of the World, a study by Anna Luhrmann, Marcus Tannenberg, and Staffan I. Lindberg, sets out four core categories of political systems: liberal democracy, electoral democracy, electoral autocracy, and closed autocracy. The position a regime holds on this spectrum is dependant on how its power is acquired, exercised, and constrained.

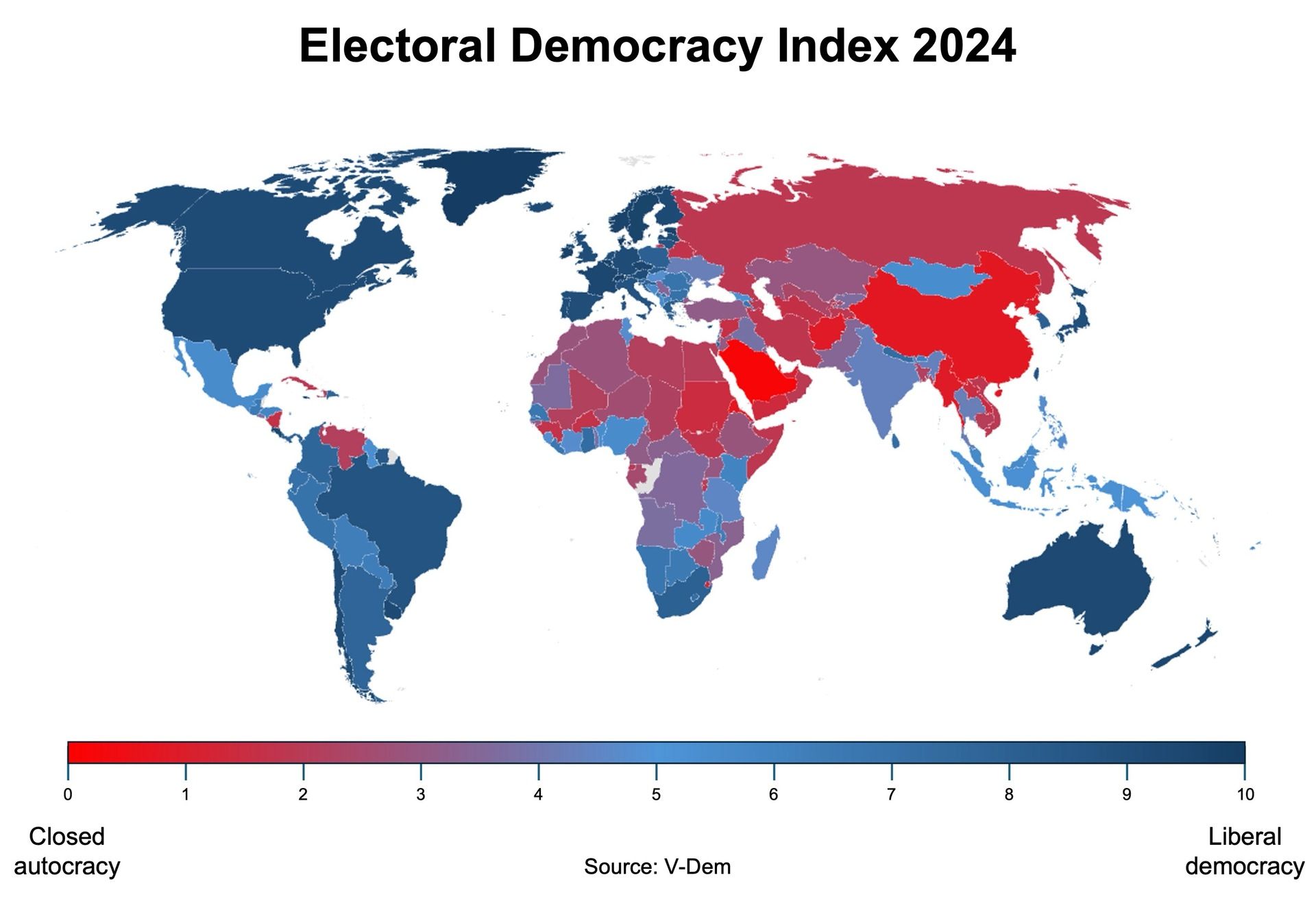

The map below shows where each country sits on the spectrum, based on data from the Electoral Democracy Index 2024. Few states sit at the extremes, with most combining elements of competition and control, shifting over time in response to political stress, economic performance, or elite incentives.

As you can see from the chart below (published by Our World in Data and based on data from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project), the world was on a trajectory towards liberal democracy until around 2016, where the trajectory began turning back towards autocracy.

This article will define and provide real-world examples of each of these regime types.

Liberal Democracy

Liberal democracies combine genuine electoral competition with strong legal and institutional constraints on executive power. Leaders are selected through free and fair elections, but their authority is limited by constitutional rules, independent courts, and legislatures with real oversight and budgetary control. Power is dispersed across institutions rather than concentrated in the executive.

Civil liberties are broadly protected, including freedom of expression, association, religion, and the press. Minority rights are safeguarded against majoritarian overreach, and the legal system operates independently of political interference. Crucially, the state is governed by law rather than personal authority or partisan discretion.

For investors and policymakers, liberal democracy offers the highest levels of predictability and accountability. Policy change is slower, but more transparent and institutionally mediated.

However, liberal democracies are not immune from erosion or reversal. Their survival depends as much on informal norms - respect for opposition, acceptance of legal constraints, and adherence to unwritten rules - as on formal institutions. When these norms erode, systems can hollow out incrementally and largely unnoticed, slipping toward electoral democracy or, in more severe cases, authoritarian practice.

Liberal Democracy Examples

Germany: Combines competitive elections with strong constitutional protections, an independent judiciary, and robust constraints on executive power under its Basic Law.

Canada: Features free and fair elections, strong minority rights protections, an independent legal system, and well-established legislative and judicial oversight.

Japan: Maintains competitive electoral politics alongside rule of law, institutional checks, and durable civil liberties, despite long periods of single-party dominance.

Electoral Democracy

Electoral democracies are systems in which political power is contested and transferred through regular, competitive, free, and fair multi-party elections. Citizens can choose both the chief executive and the legislature, and electoral outcomes are not predetermined. The ballot box remains the primary mechanism of political accountability.

Core civil liberties required for competition - freedom of expression, association, and assembly - are generally respected. Opposition parties, independent media, and civil society are able to operate, mobilise, and challenge incumbents. Electoral authorities are sufficiently independent to administer credible elections, and losing parties typically accept results as legitimate.

However, electoral democracy does not guarantee strong institutional constraint. Courts may be politicised, legislatures underpowered, and informal networks of influence significant. Minority rights and equality before the law can be uneven, allowing elected leaders to govern in majoritarian or illiberal ways despite competitive elections.

As a result, electoral democracies occupy a middle ground on the regime spectrum. They may consolidate into liberal democracies as institutions deepen, stagnate with persistent vulnerabilities, or slide toward electoral autocracy if checks erode. Their defining characteristic is meaningful electoral competition rather than institutional perfection.

Electoral Democracy Examples

India: Competitive elections with genuine uncertainty, though institutional constraints and civil liberties face periodic stress.

Brazil: Regular, competitive elections and peaceful transfers of power, alongside uneven institutional performance.

South Africa: Strong electoral competition and civil liberties, but weakened checks and governance challenges limit liberal consolidation.

Electoral Autocracy

Electoral autocracies are systems in which the electorate votes for the chief executive and legislature through multi-party elections, but those contests lack the conditions required to be genuinely free, fair, or meaningful. Political competition exists in appearance rather than reality, and outcomes are shaped in advance through structural manipulation rather than outright cancellation of elections.

Common features include systematic media bias, harassment or disqualification of opposition figures, misuse of state resources, gerrymandering, and legal or regulatory pressure on civil society. Elections may be procedurally orderly and technically credible, yet fundamentally unbalanced, with opposition participation permitted but tightly constrained.

Core political freedoms such as expression, association, and assembly are restricted, limiting voters’ ability to access independent information, organise effectively, or translate support into power. Courts and electoral bodies typically exist, but lack independence, functioning more as instruments of power than institutional constraint.

Electoral autocracies are often highly durable. By combining participation with control, they reduce the costs of repression while preserving domestic and international legitimacy. Elections act as a pressure valve for dissent and a mechanism for elite management, even as real authority remains concentrated. This hybrid structure makes electoral autocracy particularly resistant to reversal, as authoritarian consolidation proceeds behind a democratic facade.

Electoral Autocracy Examples

Hungary: Regular multi-party elections are held, but the playing field is heavily skewed through media dominance, legal changes, and institutional capture that favour incumbents.

Serbia: Elections remain competitive in form, but opposition parties face sustained media bias, pressure on civil society, and blurred lines between state and ruling party.

Turkey: Multi-party elections persist, but civil liberties, judicial independence, and media freedom are significantly constrained.

Closed Autocracy

Closed autocracies are systems in which citizens have no meaningful ability to choose either the chief executive or the legislature through multi-party elections. Political authority is monopolised by a single ruler, ruling family, party, military council, or clerical elite, with leadership selection determined by heredity, elite bargaining, appointment, or force rather than popular participation.

Political pluralism is absent or purely cosmetic. Opposition parties are banned or rendered ineffective, and civic space is tightly constrained. Media, civil society, and nominally independent institutions operate only within boundaries set by the regime. Control is maintained through a combination of repression, surveillance, and patronage, with the balance between these tools varying by context.

Legitimacy in closed autocracies rests on non-electoral foundations, including ideology, religion, nationalism, revolutionary history, or the promise of order and stability. Performance can bolster authority, but poor outcomes do not necessarily threaten regime survival so long as elite cohesion and coercive capacity remain intact.

With no institutionalised channels for political turnover, change tends to occur through elite splits, coups, succession crises, or external shocks rather than elections. Closed autocracy represents the most restrictive end of the regime spectrum, characterised by minimal accountability and limited prospects for peaceful political transformation.

Closed Autocracy Examples

North Korea: No meaningful elections, total monopoly of power by the ruling family and party, and pervasive repression and surveillance.

Eritrea: No national elections since independence; power concentrated in the presidency and military-security apparatus.

Saudi Arabia: Political authority vested in the ruling family, with no national multi-party elections and tightly restricted political participation.